February 2, 2026:

It’s been awhile since I’ve posted. Frankly, I haven’t had the heart.

I have been watching this country race toward mass acceptance of cruelty and delusion at a pace that I find dizzying. Our “president” is throwing out bile and disinformation, both on his own, and through his chosen playthings (GI Joe, Brunette Barbie, Blonde Barbie, cross-wearing Barbie–and Stephen Miller, his Claus Barbie), at a literally insane pace. He is using our hard-earned tax money for his own enrichment, and spending it on a great smorgasbord of crap that profits him and others among the super-rich, while dancing the YMCA on our Constitution—all through the befuddled inaction of a supposedly “co-equal” congress, and the blessings of a supposedly “co-equal” court that’s stacked to favor him politically, even criminally, when his endless lawsuits reach their level. We’re almost certainly also paying for all those lawsuits.

But hey, the super-rich work hard for their tax cuts and government perks…

I once met a waitress who greatly admired Trump. When I asked her why, she answered, “He tells it like it is.”

Looking at the way things are shaking out, I take that to mean he “tells it” out loud—the “it” being thoughts that we common people tend to avoid saying, because we don’t want other common people to think we’re nasty a**holes.

But I digress… So, about the atrocities in Minnesota right now. So our über-powerful “president”—with the advice and hearty participation of Stephen Miller—has singled out the least powerful people in the country to vilify, torture, and stoke hatred against: so-called “illegal” immigrants. Cheering him on from the sidelines are the above Barbies, the likes of Fox and NewsMax, and the Greek Chorus of the Heritage Society.

He sends ICE’s badly-trained masked sociopaths in huge numbers to places like Minneapolis, Portland, OR; even Lewiston/Auburn, ME, to wreak havoc and break up families, and kill a couple of citizens in the process. That so many of those grabbed off the street (or seized from their own homes via government-sanctioned break-ins) are in the LEGAL process of seeking asylum evidently doesn’t mean squat: they still have to go—to an interim “camp” as far away as possible from those who love them, then–after cooling their heels for days, weeks, months, or years–to their home country, or maybe just to some random country where they’ve never set foot.

One of our biggest issues, I think, is how we frame immigrants as “illegal.” In addition to those who are actively seeking asylum–who have suddenly become “illegal,” for no really good reason–there are others who don’t have the proper papers and are also “illegal.” And being “illegally” here, all these people are officially “criminals.”

But a great many of those without papers have been working here for years, supporting families, making a place for themselves in a community. Being productive, being decent neighbors. We have no official mechanism for these people to be permitted to stay, once somebody official discovers their papers are not in order. Because, once again, they’re “illegal,” and therefore “criminals.”

Even if they came here for the same thing so many of our ancestors wanted–a chance to make something of themselves, and their descendants–they have to go.

When we mass-deport them, who pays for that?

Why, you and I; we the taxpayers. We pay for Trump, ICE, Miller (WE PAY FOR STEPHEN MILLER–let that sink in!), all the participating Barbies, the see-no-“illegals” congress, the litigation, even the aptly-named Cash and his FBI–who have somehow gotten into the deport the “criminals” act–and for all those zip-ties, the flights, the camps, the food (such as it is), the medicine (such as it is), the guards (such as they are).

Weeeeee!! WE do all that!!!

Oh, yeah: If we break up their families, we also have to help pay for the upkeep of those left behind, because the deportee is not around to do it.

None of this is exactly an economic bonus. Not to us; not to the family, who are so often full citizens of the US. Nor does the loss of the worker profit those for whom, or with whom, they work. Nor is it an economic boost for the customers they have been dealing with. Whose houses they help build; whose food they pick, prepare, serve, or clean up after; whose chickens they pluck; whose homes they clean; whose sick grandparents they care for; whose decent lives they make possible in myriad ways that most of us don’t even think about. Until they’re gone.

But I suppose spending that money is how we thank them for their services.

Such situations are far more complicated than the insults, labels, and absolutist actions, that frame the cruelties that are being perpetrated in our names. And on our dime.

To sort out this mess to everybody’s advantage requires working together. It requires a sense of history. It requires REAL Christian values, not the fake Heritage Society variety. It requires human kindness, a will to find justice, and a functional government that respects its checks and balances. A government, dare I say, that appreciates ambition and drive, even when those who exhibit it have skin that is not lily-white.

If we could do that, maybe we wouldn’t have so many people circumventing our current unnecessarily byzantine process by coming in “illegally.”

August 14. 2025:

I was listening to a report this morning on our under-attack NPR station (because the King always attacks the media that criticize his reign) about the current court order to humanize the ICE facility in NYC. Among other things–such as granting reasonable living space to the inmates, who are “criminals” because of their seditious (See June 11 entry) efforts to immigrate, at the potential cost of their lives, to our immigrant country–the order stipulates that they receive three meals a day instead of the current two, get reasonable necessary healthcare, and are granted access to legal representation.

I’m sure the Trump administration will comply, as they always do (that’s sarcasm, for those who don’t recognize it).

I thought about the Germans during WWII, how they seemed to remain willfully ignorant of what happened in the camps in order to live their day-to-day lives. At what point, I wondered, do we all become Nazis by extension?

It doesn’t necessarily take enrolling in the Party to become a Nazi; it might just take a complicit ignorance. And when you’re barraged daily with NEWS (as opposed to common news), it’s easy to follow your preferred outrages or delights of interest. Which often excludes people you don’t know in person, even though–here in Brooklyn and beyond–they might have prepared and served you your food, cleaned up the club where you danced, polished your fingernails, staffed your local bodega, helped build your new roof, and lived two block over in that housing complex where you’re glad you don’t have to rent.

You don’t have to join ICE to be a Nazi, although it seems they’re eager to sign you on. You just have to ignore what they’re doing.

And really, what choice do we common people have in the matter? Might as well not stress over the treatment, and the fate, of people we don’t know, right?

My guess–not having lived in Germany in the 30s and 40s–is that people in many European countries during WWII felt that way.

And this disturbs me, an old woman of 77 with no real power to change the horrors I see developing around me. Human beings being abducted in the streets by masked goons; a “camp” built in an ecologically fragile area in Florida that is surrounded by alligators and infested with mosquitos, or even an overloaded, inhumane “camp” in New York City, where a sick “inmate” can have a seizure for a half-hour before somebody finally tends him, where nobody has access to a lawyer, never mind a semblance of any due process–what can I do about it?

Public protests? Check. Letters and calls to my reps in Congress? Check. Petitions signed? Entries in a blog that is mostly unread? Check and check.

Even people who have so much money that they could do something about it are doing nothing, because pissing off the King–which our Constitution insists we do not have–begets retribution. Well…doing almost nothing: Mark Zuckerberg’s growing compound in Palo Alto evidently features underground shelters to protect him and his family from whatever takes place outside. I’m sure others are using their billions equally altruistically.

Do we have to wait until the growing economic mismanagement causes someone–anyone–with power to reconsider the folly of Project 2025, which now governs us, while our neighbors are disappeared into our ever-growing cancer of concentration camps? Do we have to permanently move ourselves and our clever signs into the streets?

Or do we have to just turn our backs on the inhumanity fostered by the authors of P2025, their orange puppet King, our corrupt Supreme Court, and the soulless Stephen Miller, as they trash our Constitution and ignore the last bastions of resistance in the lower courts–so we can get along with our own small lives?

July 9, 2025:

Dear Donald:

Every time I see you, you look so unhappy. I miss your good humor, your sense of joy.

Is it…the bone spurs?

It’s upsetting to see you this way. It looks like you’ve got everything you could want. You even got that Big, Beautiful Bill. Think how rich that tax cut will make you! And there’s that billions of dollars coming to help you put immigrants away in those camps. And more camps coming! Alligator Alcatraz? Hah—nothing compared to what you’ll build with all that money!

Even those voters who wanted you to put immigrant criminals away are gobsmacked at how efficient and effective those guys are that you hired to “disappear” all these people, even the ones that aren’t criminals. Poll after poll tells you how good you are at that whole business! So much so, that—just like you promised once before—there’s so much success that everybody’s getting tired of succeeding!

So why can’t you cheer up?

You’ve put people who look so great in high positions, that when they go on camera, everybody thinks, “My, he does hire great-looking people!” Pete, Kristi, Karoline…even JD—that eyeliner really makes his eyes pop–they all look so amazing!

You’d think that alone would make you smile.

Is it…Stephen Miller? Okay, not so pretty. But sometimes you just gotta go with function over form. You have to admit, he’s a real gem, the best ever at caging those immigrants.

That should make you happy.

Is it your fallout with Elon? I know—it’s kind of like another divorce, right? Aw. But hey—You won the election—and you got to keep the money! And X! And all those “staff cuts” that his little techie-bros made happen.

So why so gloomy-gus?

You’ve got your Crypto coin. And your bibles. And bonus—you got all those super-Christians who buy them! You’ve got your airplane. And you’ve got lots of friends: just over half the Senate; even more of the House; they’ll do anything you want! And the old gang at Fox. Oh, and the Supreme Court just loves you! They love you more than they love the Constitution! And since loving the Constitution is what the French would get all fancy and say is their raison d’être—that means it’s the reason they exist—that’s a really big deal!

That should have you dancing. It’s been so long since you danced…

Is it Melania? Hmm. But look at the bright side: you’re famous, and as you yourself said, when you’re famous…

Ha! Do I detect an itsy-bitsy glimmer?

No?

Oh, dear…

Well… You’ve got the Heritage Society, and that plan they wrote for you, and they even bring you all those nifty proclamations you just have to sharpy your name to. Why, you don’t even need those boring Daily Briefings, because they take care of everything. Amiright?

Donald??

How about this: You’ve got all those countries quaking in their boots, if countries have boots, because of your Mighty Tariffs. And all your buddies at Mar-a-Lago. And your golf trophy!

Is it Vladimir? Bibi? Iran? The Houthis? Oh? Just think how impressed they’ll all be, when you get that Nobel Peace Prize!

So…why do you look so unhappy?

June 11, 2025:

Today, I painted this on a piece of posterboard:

It’s not criminal

to seek

SANCTUARY

From Violence and Inhumanity

Nor to give it.

It’s a sign for Saturday’s protest. The protest is themed “No Kings,” to counter the over-the-top military parade scheduled to grind through the streets of DC to celebrate “Flag Day”—and Trump’s birthday. (For the record, the sign’s reverse shows a drawing, the rear view of a certain naked monarch. Caption: The Emperor Has No Morals.)

In honor of the firehose of new atrocities flooding from the Oval office, the Sanctuary statement covers the latest dubious attempt to Make America Grate Again. In truth, we’re really Making America More Cruel, but that doesn’t reduce to MAGA. Not clever enough for this circus sideshow administration; they deliver their cruelty with snide—like “If you spit, we will hit”—so it will come across as yet another distracting bit of performative art.

Whoopie! Fun! Squirrel!!!

So here we are, poised to send soldiers trained for combat to quell a US protest against ICE agents. They don’t carry rubber bullets, unless combat has changed a lot since my day.

What could possibly go wrong…

I won’t discuss the obnoxiousness of sending in the National Guard over a governor’s objections for a relatively small and localized protest that should—and could—be handled by local cops. And I won’t bloviate further on the offensiveness and danger of adding active-duty Marines to the mix. Cuz, you know…deliberate provocation is standard for our Bully-in-Chief.

I’m truly sick of the “(Dark-Skinned) Immigrants are CRIMINALS” mentality being foisted on our country by a government of comfortable, über-privileged white offspring of immigrants who, when they came to the US, basically just had to prove they didn’t have TB.

Yes, those white ancestors—who weren’t brought here in chains, and didn’t own this land before righteous European settlers landed and marched them off said land wrapped in smallpox blankets—all came to our shores to find a better life. Most of them worked like hell, at terrible jobs, to create one. Why, Trump’s own Granddaddy Friedrich, a poor German immigrant, made his fortune with hard menial labor during the Gold Rush by running a brothel for miners.

My point is, immigration opportunities were there back in the days of our forebears (with a few exceptions, like the Jewish refugees on the disastrous 1939 voyage of the St Louis). Coming to this country in my great-grandpa Ahinger’s time was simpler than marching through the jungle for months with your family in tow, following guys you paid with your life’s savings, who still might rob and/or attack you, then surviving the Darien Gap, where others rob and/or attack you, then swimming the river, then stumbling out into the arms of US border agents…

To give due credit, just to pack up what you can carry and decamp to a new country in a crammed-full, stinking boat had to take a lot of despair, ambition, and nerve, not to mention a resilient stomach. Our white ancestors had to be truly motivated by their circumstances to do it.

But to come here via the route taken by so many of today’s Venezuelan refugees and their fellow travelers…Why would you even consider that unless you were flat-out desperate? And if you survive that final swim, and you sit at the desk to make your case for sanctuary, and you get your glimmer of hope—your marching orders for government check-ins…

Well, then you have to worry about getting and keeping that terrible job—or two, or three—long enough to get to something better, to safety; to, if possible, legal.

Just like our ancestors did. The job part, that is.

But now, poof!—It’s dangerous to meet those check-ins. No matter who you are, what you’ve lost, what you hoped for; no matter how determined you are, how hard you work, how much hope forced you to take this whole overwhelming journey to begin with… You wind up handcuffed, without due process. Which, incidentally, is unconstitutional.

And you’re not the only target:

Suddenly, it’s a crime to contribute peacefully to the economy for twenty or thirty years, to raise a family, send your kids to school, build your small life, to become an American in everything but the possession of a paper. You are a criminal, you lead gangs and eat people’s poodles, and nothing you say will change that because you have no right to plead your case.

I am ashamed of my government. My immigrant country. We are spending billions to insult and criminalize hard-working people. Billions, to tear families apart. Billions, to send fathers and mothers and students to horrific holding pens. The white, comfortable, über-privileged offspring of immigrants are perpetrating extreme cruelty against immigrants.

Whom they consider weak, because they can’t fight back.

I wonder how they would fare in the jungle, in the Darien Gap, in the Rio Grande?

March 26, 2025:

I lugged two heavy packages, mostly kids’ books, to the local post office today to mail them to the grand-girls in The Netherlands. There wasn’t much of a line when I started, but there was only one clerk–the Asian woman who calls me “Grandma,” and whom I refer to as “Granddaughter”–and she was working all the mail, as well as the passports.

She’s amazingly efficient. She’s been there at least as long as I’ve been in Brooklyn, which is since early 2008, and she’s also unfailingly civil to all in spite of the craziness of the fully-international crowd she serves. Even so, after she processed a passport and served two other customers (one had brought an item to be returned to a store in its original plastic bag with no mailer, and was taken aback when she was nicely informed that it couldn’t go out that way, and she’d have to buy one of the big plastic envelopes available at the window or provide her own), the line behind me was doubling on itself. And this was mid-afternoon, mid-week, when the post office is normally all but deserted.

She hefted my first box. “I can’t say anything, but Uncle Trump has made a few changes,” she said.

“Is that why you’re by yourself today?”

She rolled her eyes and didn’t reply. “I should tell you this–and I don’t want to lose you as a customer, but the price your children will pay for this on the other side is going to be very much higher. You might want to think about this.”

I shrugged. “I can’t do much of anything about it now, I’m afraid.”

“Yes, but–and I really like you, and want to keep your business, but you might think about it next time.” She processed the first package, then the second, quite efficiently. Then she looked up at her computer and plugged in some numbers. She gave me a figure–“This is what they are supposed to pay.”

It was astonishingly high. “I hope not,” I said.

She shrugged, “This is what it says it will cost. You should ask them what they have to pay.”

I said I planned to do just that. I paid her the $200 it cost to mail the boxes, whose contents were listed at a total of $54, and told her to get some rest.

When I got home, I evaluated the experience, as I always do. I’m always positive about the staff–with the single exception of a young woman who was new, and obnoxious to everybody she served (it was the last time I saw her; she obviously hated the job, so I assume she didn’t show up the next week–or maybe the next day).

I wrote:

“The service was great; it always is with this experienced and efficient employee. HOWEVER: she was the only one working, with a line that essentially went out the door–and she was also in charge of the passports. I was amazed at her perseverance and good will, considering the stress that has to be grinding on her.

“And the charges for my packages seemed higher than usual; also, she warned me that the cost to my kids who will be receiving these gifts will be higher. She couldn’t discuss it, but I gathered both the absence of others working and the costs can be laid at the feet of a government trying to make service so bad that we citizens are just dandy with privatization. Which I’m NOT.

“So I’m waiting to see what the reciprocal costs will be to our president’s stupid tariff war, and trying to get my head around how cutting staff at already understaffed post offices will “streamline” the service.

“In the meanwhile, the physical facility is in its usual horrible shape, unkempt and grubby, with black mold in evidence both up front and where the staff have to work. I understand that has to do with the landlord trying to oust the office, but it still seems unfair to the staff to have to work in these conditions.

“I think I understand why Dejoy resigned without comment. I imagine, even with his many faults (he was, after all, the first link in the Privatization scheme), even he was pissed about the micromanagement planned in the name of our so-called president.”

I don’t expect an answer. In the meantime, postal service employees are marching to keep their own jobs, and to fight the privatization of the service. Good luck, folks: it’s heartening to see somebody standing up to the power.

March 10, 2025:

An old poem (in the public domain) has been bouncing around in my head as I watch what’s going on in Washington DC.

Democracies fall; kingdoms die; countries morph into theocracies, autocracies, dictatorships, and sometimes…into democracies. I realized that back in high school, when I chose this as one of my poems on just that subject for National Forensics.

Funny, isn’t it, the vivid pictures that poets can paint…

Four Preludes on Playthings of the Wind

1878 – 1967

The past is a bucket of ashes.

1

The woman named Tomorrow

sits with a hairpin in her teeth

and takes her time

and does her hair the way she wants it

and fastens at last the last braid and coil

and puts the hairpin where it belongs

and turns and drawls: Well, what of it?

My grandmother, Yesterday, is gone.

What of it? Let the dead be dead.

2

The doors were cedar

and the panels strips of gold

and the girls were golden girls

and the panels read and the girls chanted:

We are the greatest city,

the greatest nation:

nothing like us ever was.

The doors are twisted on broken hinges.

Sheets of rain swish through on the wind

where the golden girls ran and the panels read:

We are the greatest city,

the greatest nation,

nothing like us ever was.

3

It has happened before.

Strong men put up a city and got

a nation together,

And paid singers to sing and women

to warble: We are the greatest city,

the greatest nation,

nothing like us ever was.

And while the singers sang

and the strong men listened

and paid the singers well

and felt good about it all,

there were rats and lizards who listened

… and the only listeners left now

… are … the rats … and the lizards.

And there are black crows

crying, “Caw, caw,”

bringing mud and sticks

building a nest

over the words carved

on the doors where the panels were cedar

and the strips on the panels were gold

and the golden girls came singing:

We are the greatest city,

the greatest nation:

nothing like us ever was.

The only singers now are crows crying, “Caw, caw,”

And the sheets of rain whine in the wind and doorways.

And the only listeners now are … the rats … and the lizards.

4

The feet of the rats

scribble on the door sills;

the hieroglyphs of the rat footprints

chatter the pedigrees of the rats

and babble of the blood

and gabble of the breed

of the grandfathers and the great-grandfathers

of the rats.

And the wind shifts

and the dust on a door sill shifts

and even the writing of the rat footprints

tells us nothing, nothing at all

about the greatest city, the greatest nation

where the strong men listened

and the women warbled: Nothing like us ever was.

December 27, 2024:

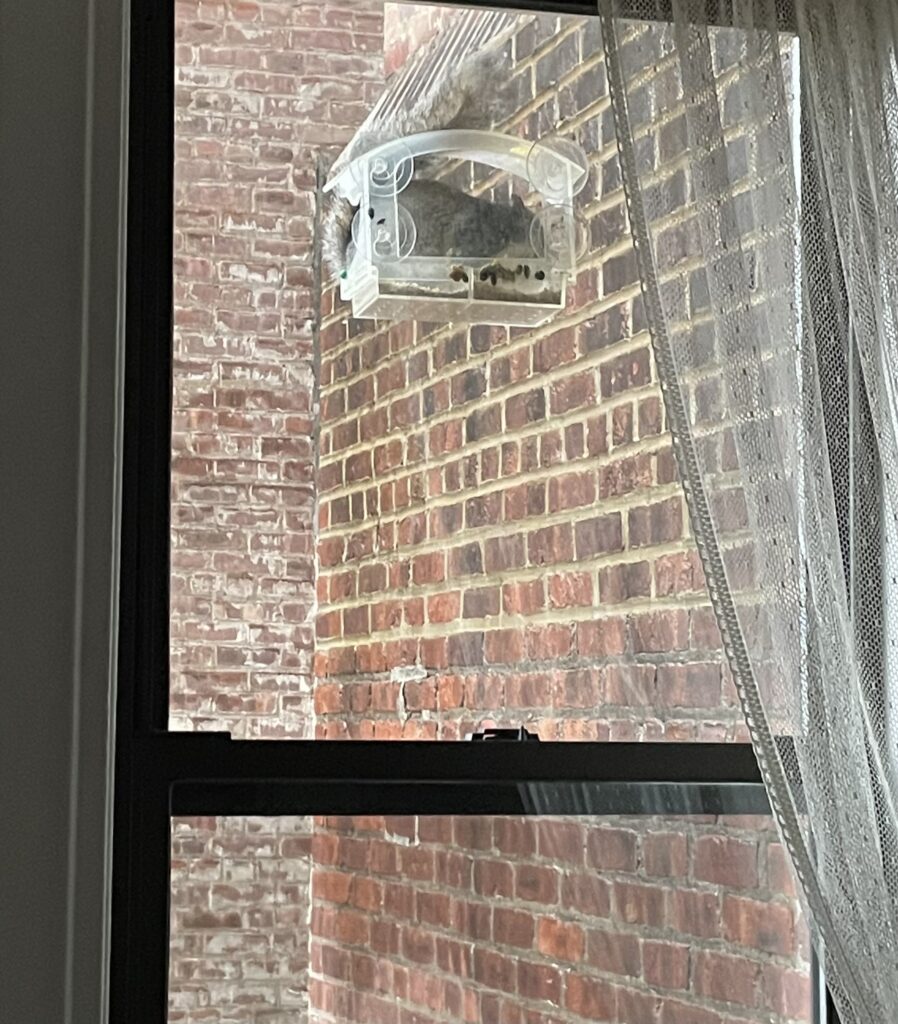

Two and a half stories of brick and glass; no overhanging trees. Sigh… (See 9/29, below…)

Nov. 6, 2024, Politics on the Micro Level:

Yesterday, I got up at 4 a.m. to work as part of Vet the Vote, an effort to recruit military veterans to help work the polls.

I was assigned to an old American Legion on Avenue X, a neighborhood that, when the hall was built in the 40s, was primarily Italian. Now it’s mostly populated by folks who came to Brooklyn from various corners of the old Soviet empire. Our interpreters were Russian.

The hall was not ideal for voting. It was a longish room, with a bar and poker table at the far end and a huge, unmovable pool table toward the front. There were five portable tables lined up on the left-hand wall.

The first was mostly covered with random stuff like extra “privacy sleeves” to cover the ballots, information leaflets, poll-worker instructions, and minor detritus that wouldn’t fit anywhere else. The second, third, and fourth tables were assigned, one district each, to the voter check-in clerks. The fifth belonged to the coordinator, and his supplies.

The middle of the room was filled with what, at first, looked like entirely too many privacy booths, where voters would mark their paper ballots. Within reach of these was a file of chairs lining the right-hand wall for tired voters and poll workers.

Then there was our section—the ballot scanners. We and our three machines were sandwiched between that behemoth of an oak-and-slate pool table and stuff you might expect to line an end wall in an American Legion, including a beer-and-soda vending machine and a big out-of-commission motorcycle. Our scanners were there because it was close to the electrical outlets—and because it was the only space left for them.

The ballot scanners are supposed to be private; they are supposed to have several feet of clearance. Ours—because it literally would’ve taken a crane to move the pool table, and that wasn’t part of our equipment—rated a three- to four-foot aisle.

Just getting to us from the privacy booths was a challenge. From the right, voters had to thread between the chairs and the special Ballot Marking Machine designed to help those with various physical handicaps (It stopped working before noon). From the left, they had to push through three lines of voters waiting for ballots from the tables, and edge past the front wheel of the motorcycle.

Two observers from the Election Commission were disturbed by our positions next to our scanners. They recommended that we stand on the other side of the pool table to avoid observing the actual scanning. It was a solid suggestion.

In theory.

But in practice, most of the more than 1000 citizens who turned out were new voters. Many of them had registered to vote specifically for this election—for Trump.

In theory, I shouldn’t have known they were voting for Trump. But the NYC ballot is not easy for newcomers to understand without reading the fine print. Especially when English is your second language, and you have to figure out what “vote for one” means when you see the names of both presidential candidates twice on the “president” line, because here Trump is listed with the Republican Party and the Conservative Party, while Harris is with the Democrats and The Working Families Party.

Many, many of our voters marked both options for their candidate. Which made the scanner spit their ballots out, declaring that the voter had “marked more than one oval for a candidate.”

It fell to us scanner personnel to figure out what the problem was—which meant examining the ballot, a process that should in theory take one person of both parties. In practice it meant a Democrat who manned the scanner, perhaps wedged between a wheelchair-bound voter next to the defunct motorcycle on one side of her aisle, and a voter with a walker on the other, facing a line of waiting would-be voters, had no immediate access to a Republican scanner-manner.

When a ballot problem couldn’t be remedied, we had to explain the issue, put the ballots back into a “privacy sleeve,” and send the poor voter back to their district’s table, where they’d turn in their unusable ballots for clean ones. Which they would carry back to the privacy booths to re-mark. So it turned out that we did need all those booths.

We had a lot of scrapped ballots, which had to be put into specific receptacles and logged in as deactivated.

As I was about to leave for my lunch break, a wiry grey-haired woman broke from the crowd, waving an Affidavit Ballot, a non-scanning ballot that clerks provide voters who can’t be found in the registration records. “What do I do with this?” she demanded.

“You mark your vote,” I said, “then put it in its envelope.”

“So who do I vote for?”

“I can’t tell you that–you have to choose your candidates.”

She frowned. “I gotta fill all these blanks on this envelope? It says I gotta put my birth date. Nuh-uh! My birthdate is my own damned business—it’s personal! I don’t have to do it.”

Just then, one of the Election Commission observers I’d met earlier passed by. I pulled him over. “This gentleman can tell you anything you want to know about it,” I told the woman brightly. I gave them a smile and left for lunch, stifling a grin. Let him deal with this secrecy issue…

When I returned a half-hour later, both of them were gone.

I realized, by the time I left Avenue X at 10 pm, that Trump would probably win. This voter turnout, from the new registrations to the polls, was very well-organized. The Democrats, in contrast, seemed far less engaged on this important micro level.

Several women whose ballot errors I helped remediate—lovely, sincere individuals—assumed because I was so supportive of their new voting efforts that I was Trump-friendly. “We must pray this turns out right, or we lose our country,” one told me. Another said, “If he wins, I will put these ‘I voted’ stickers all over myself and dance.” Yet another said, “Good luck to us! This is SO important for us all!”

The men were more restrained. Many seemed morose; some angry. Most appeared serious, determined, and proud of their first big foray into democracy.

This morning, the media are jumping on the Democratic party for not coming out more strongly. I agree with much of this. But I also realized by the end of the long night that whatever Democrats did, they were spitting into a whirlwind of misinformation, from Trump and his media and surrogates, but also from the modern—or perhaps ancient—predilection of our flawed human minds to grasp for simple solutions to complicated problems. It is easier to conjure enemies for us to battle, it seems, than to bring us together with positivity.

Perhaps I’m just depressed this morning, but I’m not sure anything can effectively counter forces like that.

September 29, 2024:

There was a frenzy of shrieking outside the dining room. Male cardinals are noisy, especially young male cardinals. This one was not fully red, and he wanted, needed, demanded the seed in my feeder.

But the dove, sleek, regal, just…sat. Not foraging; simply guarding its kingdom from this Little Twit, with his spiked pinkish feathers and punk swagger.

This dove radiated power.

Another dove, who had been feeding before it, departed, wings whistling, when it arrived. Yet another—pale-grey-brownish, puffy, most likely young, certainly foolish—tried to squeeze in beside it, but flapped off in disarray after an adept peck to his head.

It seems that “peaceful” reputation might be exaggerated.

So…the teenaged cardinal nattered in vain as the big dove sat. When I walked to the window, the dove placidly turned a bright, blue-lined black eye on me.

The young cardinal squawkled off.

My bird feeder is suction-cupped to our second-floor apartment’s dining room window. Technically, co-op rules say we’re not supposed to have one. I first flouted those rules a few years ago, when I hung a cylindrical plastic seed tube from the bottom of the fire escape above our small kitchen balcony. It seemed a fine place to put it. Unobtrusive from the outside, easy to see from the inside when I puttered over the stove. Above ground level, away from urban fauna. What could possibly go wrong?

The first month, it brought flocks of birds—cheeky sparrows, chickadees, red-headed house finches.

Then the squirrels discovered it.

It was a “squirrel-proof feeder.” Right. Those furry little monsters are smart. And persistent. Perhaps you’ve seen this guy’s backyard squirrel obstacle course?

I spent a week climbing out my kitchen window to readjust and refill the feeder. Then, one day, I found the cylinder on the balcony floor, empty, next to a tidy pile of raccoon poop.

I sighed. I had met my match. I gave the feeder away, and gave up kitchen birdwatching.

For years, I missed the birds. When I was leveled by Covid in March of 2020, I listened to the bird population, burgeoning in our new car-less world, and I longed for them. Perhaps the sight of those little winged miracles could heal me—nothing else could, back then. But I was too weak to battle squirrels and raccoons; I couldn’t even climb out the kitchen window. Forgetaboudit, I told myself–which wasn’t hard, what with the brain fog.

Last fall, I remembered. And I decided to try again. This time, I would hang a feeder on a truly squirrel-proof window.

We had suction cupped one several years ago to the window of my mother-in-law’s third-floor assisted-living apartment in Maine. She loved it–except for the doves; they were too big and ate too much, she insisted. She struggled up from her armchair to rap the window until they left.

Eventually, at 102 years old, she grew too frail leave the armchair easily. We bought her a laser cat-chaser, and she shooed them off at a distance with the beam. I felt guilty about the laser. Poor doves. But Ev warmed to the sport.

Ultimately, when Hospice replaced her armchair with a bed, the doves returned. I quietly put the chaser away and kept the seeds topped off.

I digress. The point is, I found that suction cup feeders worked. So last fall, I bought one and conned my long-suffering husband into hanging it on the top pane of that dining room window.

Our windows are old, the hardware cranky. Poor Paul. It was not an easy job. Especially without a balcony to install it from outside. But no balcony did mean no squirrels or raccoons.

The seed sat undiscovered all fall and winter. Then, this summer, it had its first customer—a dove. I walked up to the window, and the bird eyed me brightly, fearlessly.

I told Paul, “Your mom’s here.”

Hey, who knows what comes after this life? If there’s a Purgatory for minor infractions—like maybe chasing doves from your feeder with cat lasers—you just might come back for a lesson in empathy, right?

I’ve come to agree with Ev, though: Doves eat a lot.

About a week after I met the dove, I walked into the dining room to see a brilliantly red, orange-beaked cardinal pecking away at the sorely dwindled seed. He saw me and flapped off, complaining…well, like a male cardinal.

Later, a female cardinal—lovely muted grays and pinks, bright orange beak—landed daintily on the feeder and sorted through the seed remains.

The next day, we refilled the feeder. Or Paul did, climbing on a step-stool, hanging an arm over the top of the horrible window, dumping seed from a measuring cup into the platform.

To his credit, he didn’t rush off to buy a cat-chaser.

Now we have a variety of cardinals. A few adults. Two adolescent birds, one male—the Little Twit—and one female. Twit has progressed from pink to red, and the feathers above his new black mask look disheveled, like the young dove’s after his royal elder pecked his head. Maybe somebody pecks at him, too; I would be tempted, if I had a beak. Especially after that day when he found the feeder empty, and sat shrieking on the window sill for several minutes, glaring at me through the pane.

The adolescent female’s color remains a slightly paler version of her mother’s, but her colorless baby beak has turned bright orange.

And there are new, very young birds. Just yesterday, a mature female visited the feeder. Then two little cardinals, too young to classify, flapped and landed, one at a time, in her place while she watched from a nearby wire.

All these cardinals still battle for the seed—respectfully—with the doves. The young dove is looking adult, although he still has a featherless dent on the top of his head.

I have yet to see any smaller birds at the feeder. Filling the thing has become a twice-a-week task. Poor Paul.

I just sent him a link to a website, and labeled it “My birthday present???” It leads to an Etsy page advertising big wooden bird feeders that can be installed in a window, and filled from inside the room…

April 27, 2024:

Names and Games

On Monday afternoon, in a big, nondescript room on the fourth floor of the Brooklyn Board of Elections, six of us crowded around a table. We stared at the computer monitor in the center, operated by a BOE employee.

“There’s the curve on the first letter,” I said. “Can we see the petition again?”

The computer guy tipped a fat bundle of green petitions our way, and we three members of Team New Kings Democrats examined the signature on the first line. “It looks the same,” said the teammate on my left. The teammate on my right pointed his pen at the signature on the official voting record on the monitor. “The top’s cut off here, but you can see that his letter rises to a point, too…”

The man on the other side of the table, representing Team Brooklyn Democratic Party, shook his head. “Not a match.”

The Board’s assigned Referee, who sat behind the computer guy, looked from the green petition to the monitor. “I agree.” As Referee, her word was law, unless we appealed the decision to a judge at some later time. The teammate to my left made a note on her iPad. The teammate on my right sighed, then read the second voter ID number on his laptop. The computer guy clicked the second official signature onto the screen.

A game?

Depends which side you ask.

It’s a long story, confusing even to us at that table. Or the groups at the other tables scattered around the room.

A couple months ago, our friend Gina recruited Paul and me and two other neighbors to petition to join the Kings County Democratic County Committee. It’s the lowest rung of the political ladder of the Brooklyn Democratic party. She gave me a clutch of empty petitions. “You’ll only need a total of fifty signatures for all four of you, and you’ll be County Committee members. Get five more just in case any turn out to be invalid.”

County Committee members, all unpaid volunteers, “rep their block”—we’d represent a neighborhood two streets wide and five blocks long in Brooklyn Assembly District 42. We’d go to a few meetings, vote on a few things. The County Committee would comprise a couple thousand of us; it’s not likely we’d become drunk with power.

Democracy, at the street level.

Gina’s a retired lawyer and lifelong Brooklynite, a member of New Kings Democrats (NKD). She’s a good person, a liberal activist, not easy to turn down. “You won’t have to actually run for the office,” she said. “Unless you’re opposed by County. We can discuss that later.”

“What? Why would anybody want my seat, if we do practically nothing and have no real power?”

“Well, the problem is…“ Gina named the Brooklyn Party Chairman.

The current Party Chair is a powerful woman; she’s a member of the NY State Assembly—New York’s House of Representatives. She’s Majority Whip, and belongs to, or leads, several important state committees. She’s also our Assembly District 42 State Representative.

At 52, she’s accomplished in her own right: a child of Haitian immigrants, she’s earned two Bachelors degrees, a couple Masters—former teacher, former engineer, former investment banker. Current law school graduate–which is appropriate, because she’s litigious. Which has everything to do with this story.

As I said, the committee we’re aspiring to can accommodate thousands of members—Brooklyn is populous and largely Democratic. But only half of the seats are ever filled. So you’d think the Party would welcome all Democrats to this supposedly-democratic Democratic process, right?

But New Kings Democrats and their allies have never really been invited to the Party, so to speak.

The group was new New in 2008, founded by idealistic Obama volunteers. Their manifesto states they’re “committed to bringing transparency, accountability, and inclusionary democracy to the Kings County Democratic Party.”

The Kings County Democratic Party didn’t welcome the group. In 2016, under an earlier Party Chairman, they were outright dismissive—so much so that they literally dismissed a key meeting prematurely when NKD members and other reform groups put up a list of transparency and anti-corruption measures for a vote of the Kings County Democratic County Committee. After some heated back-and-forth with no action, Party voices were raised; reformers countered with chants.

BOOM—Meeting adjourned. When it reconvened…those reforms? Fuggedaboutdit.

Now, the Party has answered the group’s latest attempt to democratize it by filing lawsuits against seven candidates the NKD endorsed for District Leaders in six Assembly Districts.

District Leaders are the next rung of the County Committee—it’s a big step into Democratic Party realpolitik. In fact, the Party Chair herself started her political career in 2010 as a District Leader. Which might explain why she’s suing to keep reform-minded candidates away from a position where they might attain power to advance their agenda.

The Party Chair and her party are doing this by challenging nearly every name on the ballots that NKD-endorsed District Leader candidates collected. There are official codes for signature no-nos: NE (Not enrolled as a Democrat), OD (out of district), PR (Printed, not signed), F (forgery)—and ad-hoc notes for “non-matching signatures”: my teammate working the spreadsheet just noted “sdm” (signature doesn’t match) with each decision by the Referee that an autograph didn’t fully match the one on the voter rolls. It was a gentler term than F for suspected forgery.

Whatever one called it, suspected Forgery was the main thrust of the Party’s objections.

Each green petition sheet has ten lines. Each line has a printed name, address, and signature. The petitioner is a Witness; they sign the sheet, swearing the signatures are real. Paul and I and our two co-candidates needed only 50 valid signatures. District Leaders need 500 each, and some collected twice that number.

It’s not easy to collect even 50 signatures. We slogged through a downpour, knocking on registered Democrats’ doors. We got turned away. A lot. We raided apartment buildings, begging every Democrat on our list. Signers scribbled; many signatures were illegible; all were squeezed into a sort of half-height-line, to make room for their printed names beneath.

I thought it wasn’t right for the Party Chair to sue to throw NKD-endorsed District Leader candidates off the ballots after they worked so hard to gather all their signatures. And so it was that I volunteered three hours at a table in a nondescript room on the fourth floor of the Brooklyn Board of Elections last Monday.

It was educational. It was also tedious, an uphill battle. Team New Kings Democrats, Team Brooklyn Democratic Party, the computer guy, even the Referee—not one among us was a real handwriting analyst. Did all our signatures match the signatures made years ago when these folks signed the voting rolls? Did 80-year-old Mary Jones still sign exactly as she did at 20? Did Hector Sanchez sign differently in a half-inch space than he did on an official form? Will Arlo Brown write exactly the same with my clipboard on his knee as he did on that sheet at the polls 15 years ago?

It was an amateur judgement call at best.

Again, again, again; table by table; line by line. Five days, a rotating raft of volunteers, several paid Election staff—all these unprecedented challenges. The expense to NKD and other members of the reform coalition; grassroots David lawyering up against Brooklyn Party Goliath. The Democratic Party blithely spending money raised from Democratic donors to insult, accuse, drain money and time from, and disenfranchise, other Democrats.

Hmm…

Maybe it’s time to reform the Brooklyn Democratic Party.

November 11, 2023:

The Free Shuttle Bus

Last Sunday, I grabbed a plastic bag of ashes and dead roses and walked to my subway station, to find it closed.

The stuff in the bag was the remains of my Dia de los Muertos altar, a remembrance I arrange in our dining room every October: pictures, flowers, candy, and little Mexican totems set around a bowl of sand. The dead, being generous, welcome all to eat the candy, and to stick paper slips with names of lost loved ones in the sand.

I disassemble my altar sometime after November first: I box the pictures and other staples, then burn the name slips. I bag the dead flowers with the ashes, and take the subway to Coney Island—a 20-minute ride—where I send them off on the tidal waves, a fitting goodbye.

Sunday, however, a sign on the locked station door informed me that it and all nearby stations on the Q line—up to Prospect Park, down to Coney Island—were closed for track repair.

We could, it said, take a Free Shuttle Bus to all the stops by walking three blocks to a special bus stop on Ocean Avenue.

The Free Shuttle Bus is great, in theory. In reality, it’s straight out of Dante. It’s a slow bus ride that parallels the Q line: passengers hate the crowding, the traffic, and the agonizing pace. Bus drivers hate the unfamiliar routes, and the passengers, who just want to be on the train. Everybody hates the drivers, especially when they get lost—as often happens.

I considered biking the distance. But it was afternoon, the first day of the time change, so I’d ride back in the dark on a badly-maintained path and roads clogged with traffic. I didn’t want to die, so I gritted my teeth and set off to Ocean Avenue for the Free Shuttle Bus.

A sign at the special bus stop told me the Free Shuttle Bus would go to King’s Highway—halfway to Coney Island.

And…after that?

The bus came ten minutes later. It was full of passengers who, like me, would normally ride the Q subway. Every age, from every corner of the world, we rode in grumpy peace. The ride was glacial, but uneventful. Until we reached the King’s Highway subway station.

There, we disembarked, and I prayed that maybe the subway was actually still open from there to Coney Island in spite of the sign on our station. Alas, no. We were herded across the street by a guy in a neon-orange vest to stand by a closed bus.

After a few minutes, the guy in the neon-orange vest noticed that the bus had a driver inside. He knocked on the bus door and ordered the driver to take us to Coney Island.

“I’m going back to Prospect Park,” the driver said. “I been on all day. It’s my last trip.”

“You’re going to Coney Island.” The guy in the neon-orange vest waved us into the bus.

The driver lasered the guy with a toxic glare, but the guy stood unscathed behind his neon-orange armor. A helpful lady with a Russian accent told a Mexican family bound for Prospect Park that the bus was now going to Coney Island; they hustled themselves out. The driver jerked the door shut, locked himself in his plastic compartment, and we ground away from King’s Highway.

Ten minutes later, three befuddled passengers—a slight, elderly man and two pale middle-aged women—sidled down the bucking aisle to the front. The elderly man knocked on the door of the driver’s clear plastic compartment door. “Ve must get off,” he said, his accent heavy and desperate.

The driver stared ahead, jaw set, unspeaking. Driving.

The man rapped again. “Ve MUST get off HERE!” Nothing. He then added, “Vhere ARE ve????”

Nothing.

The elderly man rattled the clear plastic compartment door. The driver stared ahead, unspeaking. Driving.

The helpful lady with the Russian accent went to the plastic door and knocked. Nothing.

She spoke gently to the elderly man. “You are maybe on the wrong bus? This is a Free Shuttle Bus. Where do you want to go?”

The elderly man asked her, “Vhere are ve???”

“We are going where the Q train goes. This will stop in Sheepshead bay, then Brighton Beach, then Coney Island.”

The elderly man looked horrified. His two companions spoke with him in a mysterious, guttural language.

The helpful lady patted his hand. “You are I think on the wrong bus. We will stop soon.“ She pressed the stop signal. The sign up front flashed “Stop Requested.”

The driver, unspeaking, drove past the bus stop.

The elderly man wailed. The two pale women gasped. They muttered mysterious guttural words.

The driver stopped two blocks later, at a red light. He did not open the door. The elderly man pushed and pulled at the door handle. The helpful lady rapped on the plastic compartment door. The light changed; the driver stared ahead, unspeaking. He drove.

The helpful lady frowned. The elderly man, wild-eyed, shouted, “He is doing NOTHING! Ve are PRISONERS!” The women grew paler.

The helpful lady shook her head. “Pff. You must perhaps take a different bus at Coney Island.”

Someone pressed the stop signal; the sign once again flashed “Stop Requested.” The driver drove past the stop, unspeaking.

The man kicked the plastic compartment door. “You must let us out NOW!” The two women nodded vigorously.

The helpful lady looked up the number of the MTA help line. She tapped it into the elderly man’s phone and handed it back to him. “Tell them,” she said.

He shouted at the phone, “You must help us. The man keep us prisoner on this bus. Ve are TRAPPED here. Ve are KIDNAPPED!!” He said to the helpful lady, “Vat is this bus number?” She pointed to the number above his head, then spelled it out to him.

“He vill not stop,” the man repeated. “He vill not talk. He vill not tell us vhere we go. Only drive.” He nodded to the pale women. “Ve are three.”

He sighed, nodded again, hung up. “He say go to Coney Island, take other bus there.”

The helpful woman nodded. We drove in silence for twenty minutes, then landed, at last, in Coney Island. The driver jerked the door open, then locked himself back behind his clear plastic compartment door.

The elderly man shepherded his charges off. As he stepped out, he turned back to the driver. “You are NOT A GOOD MAN,” he told the driver. “You are…FUCKER!!”

One of the pale women cursed the driver in her mysterious guttural language. The second woman sneered and gave him the finger.

The driver sat in his plastic compartment, staring ahead, unspeaking. The rest of us filed out in silence. The helpful woman took the elderly man’s elbow and led him to a bus stop. The women followed them like pale ducklings.

I walked up the street to the beach with my plastic bag of dead roses and ashes. At the shoreline, I opened the bag and shook the contents into the surf.

I was buffeted by a flurry of wings, as a flock of seagulls dove on the rose heads. Most dropped them immediately in disdain; a few flew off, bearing the flowers like prizes.

One stood fast before me in the dying sunlight, a bruised yellow petal drooping from its mouth; it lasered me the same malice the driver had given the guy in the neon-orange vest at King’s Highway, what felt like hours ago.

The tide scooped up the remains of my altar, and I bid goodbye to my generous lost souls, and watched a magnificent red sun drop into the sea.

Then I turned and walked down to the street, to search for the Free Shuttle Bus that might take me back to Ocean Avenue.

October 16, 2023:

Overheard a couple days ago in Park Slope:

Dude, emerging from the PetSmart store, to his grinning terrier:

“You really shouldn’t pee in there, Charlie.”

January 1, 2023:

Yesterday, on New Years Eve morning, I picked up a Christmas package from France at my local post office.

My Brooklyn post office is a big, tattered facility whose clientele is largely English-as-a-second-language, served by an overextended staff whose own first languages often differ both from English, and those of their customers.

I find the staff supernaturally patient. Except perhaps at lunch hour, when the lines are outrageously long—not because the staff are eating (They don’t have time; now and then, a keeper throw them tablets of Soylent Green), but because most of the noontime customers are working stiffs on short lunch breaks.

Even then, though, the staff try very hard to be accommodating.

Oh, there once was a clerk–this was some time ago–who railed at his customers when they didn’t present their forms filled out, or spoke with an accent, or counted their money slowly, or chewed gum, or came on a day when his feet were hurting. He was a legend: a clerk at a post office five miles down the road, when I mentioned my local PO, gasped, “That’s where that awful man works!”

I filled out my customs forms and spoke English, so he treated me decently. But one day he complained to me, “I wish I could cut off my hands so I wouldn’t have to do this job.”

I nodded and remarked that that could be a mitzvah for us all.

He stared at me openmouthed, as if struck by a lightning bolt–or perhaps a Divine Revelation from beyond the Plexiglas. Then he finished my task in silence.

Within a month, he was gone. Retired, they told me. I’m sure I had nothing to do with it.

He was replaced by an amiable guy who spends a half-hour sending a package overseas because the system requires him to key the customs info into a computer from handwritten forms. He types one letter at a time, using the eraser-end of a pencil, which demands a supernatural patience from the customer. I send a lot of packages overseas, so if I find I’m next when his window is free, I generously welcome the customer behind me in line to go ahead.

But…back to the package from France. The package that my son and daughter-in-law sent well before Christmas, and began tracking when it had not arrived by the 23th.

First, they discovered it had been sent to Chicago. Why Chicago? Because it’s closer to France than New York.

I’m being sarcastic. However, once our postmaster herself, a young woman with an authoritative air, tracked down a package for me that I’d sent unsuccessfully to France. She printed its itinerary. “Yes, it should be in France,” she read from her printout, “but this says it’s in the UK.” She looked up at me and asked, quite sincerely, “Where’s the UK?”

Anyway, our French family’s package hit Chicago, in a masterpiece of timing, right before the snowstorm that paralyzed the Midwest. And there it rested until the skies cleared.

The day after Christmas, it landed in Brooklyn. At my post office. It went out on the truck.

Then it went back to the PO.

This worried me. Were they returning it to its senders?

Something I had mailed to The Netherlands returned to me recently. I’d made sure its business-sized envelope was correctly addressed, weighed, and properly stamped with an International Forever stamp, but I received it back two weeks after I’d mailed it. There was a printed notice pasted on the front that said “Returned, no bin.”

I brought it to the post office and asked the clerk, a very efficient Asian woman who calls me Grandma (I call her Granddaughter in return, which cracks her up), what “no bin” meant. She said she didn’t know.

“Why did they send it back? Is this a US notice, or a Netherlands notice?” I asked.

She had no idea; she’d never seen this type of notice. But from its look, she thought it must be ours. “You want me to ask the postmaster?”

“Ah…probably not,” I said.

So now, I worried that the French package might be on its way back to France, and no one would ever know why.

But no: our daughter-in-law texted that their latest tracking claimed the truck had brought it back to the post office because the address had to be “verified”–it didn’t have an apartment number. She texted a snapshot of the label that her French PO had printed: the address was complete, but the apartment number was printed smaller than the street address.

Our package delivery guy, Nguyen, knows us because he was our street postman before he moved up to the truck. He would’ve delivered it, so he must’ve been on vacation. But surely his substitute would notice the apartment number and try to deliver it again? In truth, the PO doesn’t even need an apartment number for packages in our building; they go into a locked cage in the lobby to keep them from being stolen.

For two days, I dutifully unlocked and picked through the mess in the cage. It wasn’t there.

Our French family called the general USPS number, and eventually spoke to a real human in Brooklyn. She verified that the address had to be verified. “She said it had your apartment number, but not your street address. But she said you could pick it up at your post office,” my son texted. “Maybe the label got messed up in the storm in Chicago?”

I went to the post office on December 30. I went during lunch hour–unfortunately–because we planned to go into Manhattan that afternoon. The line was long, as expected, and only two windows were open. The two clerks were also processing the odd passport application, a complicated multi-layered task.

When at last I reached a window, I showed the clerk, Peg, the picture of my kids’ label. She took down the number and disappeared into Unverified Package Country.

At the other window, my Asian Granddaughter was working on a toddler’s passport. She ducked out to take a picture of the child–which wasn’t easy, because the kid squirmed vigorously as her dad held her in front of the white screen.

The line grew. A man three people back asked me, “What the fuck is holding things up?”

“She’s finding my package,” I said. “Sorry. It won’t take long.”

Granddaughter wished the toddler’s family a happy 2023. Her next customer was an ancient man who spoke Russian. I heard her explain he had to wait to do whatever he had to do until the “due date.” He didn’t understand, so she wrote this down on the back of the paper he’d presented her, turned it over and circled the “due date” on the front, and repeated herself.

“Do data?” he asked. She turned the paper over, and pointed to the words she’d written as she slowly repeated them. “Your daughter should do this for you,” she added. “Have your daughter come.”

“Ven she do?”

“On the due date.” She turned the paper back over and re-circled the date, wished him a happy new year, and motioned to the next man in line.

“Ven she do data?”

“On the due date. Have your daughter come then.”

He moved away reluctantly, and she processed another passport application.

He stood near the postboxes and called across the room, “VEN DO DAUGHTER???”

I waited. It was 15 minutes since Peg had gone package-stalking. The man who had wondered what the fuck was holding things up was now first in line. He frowned at me. I shrugged.

“Fuck this!” He threw his hands up in the air and walked out.

Twenty minutes. Granddaughter had processed yet another application and served two more customers. The line was longer, restless, pointedly deficient in the Joy of the Season.

I waited.

After 25 minutes, Peg returned. “I’m so sorry,” she said. “I can’t find it anywhere.”

“Could it be on the truck? If Nguyen was delivering, he’d at least know our names. Is he back from vacation?

“He came back today.“ She lowered her voice. “He was sick. He had Covid.”

“Oh dear.” That wasn’t good. Nguyen smokes—a lot. I would too, if I worked for the PO. I’d also drink–a lot.

“But he is doing deliveries today,” she added. “So…maybe?”

I gave her my phone number in case she found the package. There were now a dozen people in line, excluding the ancient Russian man, who was still staring at the writing on the back of his paper as I left.

An hour later, Peg called me while we were on the subway into Manhattan. “I found it—somebody had taken it into the office.”

And so, the next day—New Years Eve morning—I waited in line for a half hour and picked up the package.

The package was undamaged, its label completely intact. Scrawled in pen next to the street address—almost over the number to our apartment—was a note that said “12/27/22—no apartment #.”

December, 2022:

Merry Christmas/Happy Holidays to all!

This year, we have learned who owns New York City.

Well, yeah. We’d seen them in subways, skirting the track edge, darting untouched beneath the third rail. We glimpsed a furry skitter on a late-night Village curb at the edge of a funky outdoor dining plaza. We noted a flash of brown in a pile of trash bags.

But rats are smart, we assured ourselves. Rats know their place.

Last month, we returned from a vacation to find a round hole in the base of a kitchen cabinet. Beneath it, sawdust. Inside the cabinet, pastas and grains leaked from torn packaging and lay scattered in little piles. We heard, somewhere unseen but too near, an insistent gnawing.

Our lives changed. There was before the rats; then, abruptly, during the rats.

If it was edible, we locked it in glass jars or stout plastic storage boxes. The Building Super spent so many days in our apartment—moving dishwasher, stove, refrigerator; stuffing steel wool around heating pipes; baiting snap-traps; filling holes in the kitchen walls with more steel wool, mixed with broken glass and cement; cleaning up; returning to fill more holes; bringing and laying sticky mats for rat traps—that we signed adoption papers for him. The gnawing in the walls grew more insistent. The sticky mats caught two rats and Paul’s left foot. Others left footprints or hair swatches on them. We saw rats in the kitchen, the heaters, our nightmares.

At last, the exterminator arrived. He pumped poison into every wall in the apartment, sealed his bullet-holes with plaster, wiped his hands, adjusted his cape, and flew out the window into the darkening city to rescue his next downtrodden victims.

We tiptoed gingerly into after the rats.

We are cooking again. There are no dirty dishes in our sink, no fallen food bits on our floor. There are sticky mats where there once were baskets of potatoes and onions. We are breathing again. We put our ears to our walls, but there is only silence. All our sticky traps are empty.

Maybe the rats are dead. Or maybe they’re just discouraged by all that steel wool, broken glass and cement they have to navigate just to reach food that’s locked away in glass and plastic.

But rats are smart. I believe they are huddled somewhere, smoking and drinking, nibbling brie and stale crackers. Reading the New York Times as they chew its edges, discussing the news that the city is looking for a Rat Ridder.

Plotting how to engage. How to subdue. How to win.

How to keep their city.

November 8, 2022:

We returned to our Brooklyn apartment Friday, after three weeks out of the country, to find a pile of sawdust under our corner kitchen cabinet. I opened the door. A round hole had been chiseled into the outer lip of the cabinet floor.

I stared at the mess inside: pastas and lentils and beans jumbled together, rice leaking from plastic bags. Little clumps of black.

Rat scat.

We’ve lived here 14 years. I’d seen rats in the streets and subways, but never in my kitchen.

I chased the Super down—calling was futile, because he never checks his voice mail (if I had his job, I probably wouldn’t either)—and by 5 o’clock, we had secured four “humane” sticky-mats designed to catch bugs and mice. The Super assured me they also worked for rats; he’d found a few downstairs while we were gone. They’d had a team painting the basement, and had had to take screens off vents so…yeah, he’d caught a few. Maybe 7 or 8. Or 10 or 11.

He’d caught one in our downstairs neighbor’s apartment. But since she’d bought a cat, he said, she hadn’t seen any. “Maybe you should buy a cat,” he said.

We won’t buy a cat. I love cats, but my kids are all allergic to them (even the son who now owns two). Growing up, my kids had other pets. Rodents. Pet hamsters and gerbils. And rats. Smart, interesting creatures. With personalities.

We once had an infestation of mice when we lived in Massachusetts. Cute little buggers. I relocated them with a humane trap my older son crafted out of an old plastic lunch pail.

Now I found myself with four “humane” sticky-mats for rodents with no relocation potential. Why make a sticky-mat “humane” if somebody kills what it traps?

“If you catch one, call me and I’ll get rid of it,” the Super assured me.

With a heavy heart, I pulled the protective covering off the sticky-mats. We put one under the hole in our ransacked cabinet, and the others in places where I might wander if I were a rat.

Within ten minutes, I heard an unearthly scream. I ran to the kitchen, where a sleek grey rat—a little small, as rats go—struggled to free itself from the sticky-mat. Paul sat at the table, looking panicked. He stamped his foot, and the rat screeched and struggled harder. “I’m trying to get him to stick—he’s breaking free.”

“Don’t stamp. You’re scaring it—upping its adrenaline. You’re helping it.”

“He’s getting up!” Paul’s voice rose. “What are we supposed to do with him?”

I called the Super. His voicemail was full.

I grabbed a sticky-mat we’d placed in the dining room and slapped it over the rat, creating a rat sandwich that screamed all the more piteously. “Oh, god–I’m so sorry,” I told it.

“Don’t touch him!” Paul said. “He’s still going to get out.” He tapped the top sticky-mat with the tip of his shoe, and the rat instantly fell silent.

“You killed it.” My stomach hurt. I can’t kill anything, except mosquitos, which I consider self-defense. I even scoop up those huge Brooklyn cockroaches with toilet paper and flush them, which I’m pretty sure doesn’t kill a cockroach because they swim, and because nothing short of a hand grenade kills a cockroach.

Paul said, “I was just trying to tamp the sticky-mat down.” He looked shaken. “He’s not dead. Let’s go get something to eat; we’ll figure out what to do with him when we get back.”

I looked down at the rat. Definitely dead. We’d killed Ratatouille.

I didn’t feel like eating. But eventually I would, and we had no fresh food in the house. And pastas and lentils and beans were not an option.

We left.

We came back an hour later. The rat was still dead. I called the Super. His voicemail was full.

I grabbed a dustpan and pried up the sad rat sandwich—not easy, since Paul had stuck the top sticky-mat to the floor with that fateful toe-tap—and took it down to the basement trash cans. “I’m sorry,” I told it. “I’m really sorry.”

There were still two sticky-mats left, so I relocated one to the spot next to the cupboard.

The next morning, I glanced into my bathtub to find the biggest, ugliest cockroach in Brooklyn. “Mother Nature hates me,” I groaned. I scooped it up in toilet paper and flushed it. And flushed again. And again.

I walked to the plaza to look for something rat-proof for storing pasta. The small dollar store there is crammed with random items: cups and saucers; umbrellas; party hats; piles of reading glasses; bright blue betta fish swimming in plastic cups. I bought a couple of stout plastic boxes.

When I got back, I gloved and masked and tackled the cabinet. Nearly every bag had been gnawed open. A brand-new package of basmati rice was shredded; noodles lay everywhere. Beans and lentils spilled from bags; macaroni leaked from an unopened box.

The only salvageable grains were those I’d sealed in glass jars; the only intact pastas were gluten-free–and no, I have no idea why. I dug out a nest of sawdust and spinach noodles at the back of the cabinet, swept, scrubbed, disinfected, and stuck the gluten-free pasta in my new boxes.

That evening we heard gnawing in the dining room. I found the handle of a wicker basket bitten through. Paul saw movement behind the living room radiator vent, and set a sticky-mat in front of it. An hour later, it was untouched, but there were shreds of chewed paper around it.

I noticed the sticky-mat in the kitchen was askew, and shined my phone’s flashlight over its surface.

It was empty, but there were four big, distinct, dusty footprints on its shiny surface.

They spelled out that quintessential Brooklyn challenge: “Hey! I’m walkin’ here.”

April 7, 2022:

Last night, the Universe revealed that the season has at last turned in Brooklyn.

I saw my First Cockroach of Spring.

I try hard to be cognizant of Nature’s beauty in all her wildlife. A deer can stop me in my tracks. I admit that’s due in part to the fear of getting too close and catching Lyme Disease (or, now, Covid19), but I do have an awe of the creature itself. A fox mystifies me. An opossum in the street sends me to Professor Google, and pictures of little possums riding on their mothers’ backs. I’ve watched the Squirrel Obstacle Course video at least a dozen times, and sent it to everybody I know (https://www.google.com/search?channel=nus5&client=firefox-b-1-d&q=squirrel+obstacle+course+youtube – in case I missed you).

I won’t eat any animal I would refuse to catch, which leaves me basically vegetarian, with an occasional side of fish, mollusks, or shrimp (not octopus; how could I eat something that’s smarter than I am?).

I respect insects, too, even the ones I find freaky: you won’t find me stomping on a spider, and I try very hard to shoo flies to the outdoors—as opposed to my husband Paul, who loves his flyswatter.

So when I saw the enormous First Cockroach of Spring on my bathroom wall last night, I did what any mature, responsible nature-lover would do: I yelled for Paul. “There’s a cockroach in my bathroom!”

He glanced in and said, “Okay…Where’s this—Jeezuz!! That’s…big. What do you want me to do with it?”

“Um…maybe capture it or something? Don’t kill it; it’ll make a mess on the—”

He mumbled something about walls being cleanable, turned on his heel, and returned with his flyswatter. “It’s been what? Three, four months since we’ve seen one of these? Where the hell did it come from?”

Where does any 4-inch cockroach come from? Ask the Universe.

Swat!

I must admit, it was masterful, if nauseating: he smacked it into my bathtub. “Thing is really lively,” he said. Swat!

“You don’t have to kill it—just throw it in the toilet.”

Cockroaches can swim. My own strategy is usually to run the monster down, trap it in a paper cup and toilet paper, drop it out into the toilet, flush it alive—usually a couple times, so it’s past some magical baffle that separates me from the sewer system proper—and tell myself I’m sending it to a happy life there, eating fecal matter with its buddies and swapping death-defying adventures.

So why didn’t I do that this time?

Once Paul had thrown the mangled corpse in the toilet—“See, he’s still wiggling. Don’t worry, I think he’s still alive…”—followed by the remaining disembodied legs and smelly unidentifiable parts, I asked myself that very question.

Maybe it was the surprise of seeing one after so long without a cockroach-sighting. I’d let my guard down; it felt like they had all somehow vanished: Poof!—no more cockroaches in this house.

Maybe it was its size. Brooklyn cockroaches are big, one to three inches of body, plus leg and antennae length (not that I actually measure them), but this one was freaking outrageous: the thought of stuffing it into a four-ounce paper cup was laughable. Even the wide mouth of an eight-ounce plastic cup, which I could’ve grabbed from our storage closet, wouldn’t have fit over the thing without squashing a leg or three, never mind those obscenely long antennae.

Maybe it was its color—don’t get me wrong; I’m not a cockroach-racist, it’s just that it was Very Dark, nearly black, and the last time I saw a Very Dark cockroach (in fact the only other time, two summers ago), it was in our living room, and it flew down from the ceiling. Which really creeped me out, because yes, they have wings, but I had never, ever seen a cockroach use them. So after Paul beat it out of the curtain where it had landed, I went to Professor Google and I learned that the American Cockroach, including that Very Dark one then expiring on the floor, can “glide” (to euphemize the horror).

That’s also when I learned that cockroaches can swim up through drain pipes. And Scientific American, no less, announced that a cockroach can live for some time without its head.

Without its head. Google it.

So maybe Paul’s right. Maybe the First Cockroach of Spring really is still alive, even though it’s missing parts.

And maybe it’s swimming up the drainpipe, past those magical baffles…

December 23, 2021:

Last Friday, I got the staples taken out of a six-inch incision wound. At the same time, in a different part of the hospital, Paul got his stitches taken out of an inch-long wound in his finger.

I’m taking more drugs than I’ve ever taken in my life—Celebrex for inflammation and pain, a stomach acid suppressant for the havoc Celebrex can cause, calcium, Vitamin D, an aspirin for blood clots, Tylenol at night to control pain. An opioid that makes me cranky and shaky.

Paul is taking an antibiotic as a precaution. He’s also taking a nap, because the antibiotic’s wiped him out. And he’s worried that the incision doesn’t look quite right.

Paul, my husband of 51 years, is a large man with a large personality. He loves to laugh, to tell stories, to wow you with facts he’s gleaned and remembered. If he’s met you, chances are he’ll remember something you said in passing twenty years later. It’s a trait he inherited from his late mother. I find that kind of memory from somebody who can never find his glasses downright mystifying.

He’s a leader, a retired CEO—much more assertive than I am. And louder. People follow him because he’s the Tall Guy, the one who radiates assurance. If you meet the two of us for the first time, you’ll remember him. Me, maybe not so much.

I love him; he’s a good man. But sometimes I feel I’ve been seduced into a mysterious competition whose rules I don’t understand.

For instance, after we both were sick with Covid back in 2020—a lifetime ago—and were finally given blood tests, his antibodies count was higher than mine. He still brags about that.

Several days ago, when I came home from the hospital after my total knee replacement, our daughter Kym brought me a big, gorgeous bouquet of white flowers. She put them in a vase with water and the accompanying flower-reviving powder, but warned that she didn’t have a lot of time to spare, so we should probably cut the ends off the stems so they live longer.

I wasn’t up to chopping flower stems, so I delegated the job to Paul.

The next morning I jerked awake to his calling my name. I limped out of the bedroom to find him holding a balled-up paper towel around the pointy-finger of his left hand. Paul takes blood thinners, and the blood was thin—and plentiful. The kitchen sink and the counter looked like an abattoir. “I think I got it to stop,” he said, and withdrew his impromptu wrapping enough for me to see the back of the finger, where the cut was obviously deep enough to require several stitches.

He had been trying to cut the stems of my flowers, he explained, and the big knife he was using hit the marble of the cutting board and skipped over the back of his left hand.

I texted Kym and explained her dad’s dilemma—did she know a good clinic close to home? She came up with a five-star-rated walk-in that was less than a mile away.

“Let’s go,” I told Paul. “If you can’t drive, Kym said she’ll rearrange her schedule and drive us.”

“It’ll be fine. We have a Zoom this morning, and I can’t miss it.”

I checked the clock. It was 8:30 a.m. “The Zoom is at 11. There’s plenty of time. You need stitches—every time you bend that sucker, it’ll break open and bleed.”

“I’ll go to the VA after the Zoom.”

“The quicker you get to it, the better. You don’t want it to get infected.”

Nope.

I threw up my hands. “Right after the Zoom, we’re going to the VA.”

The meeting was over at noon. Janina, who cleans our apartment every couple weeks, had arrived, and Paul showed her his wounded finger.

“That looks bad,” she said.

“Let’s go,” I said.

“I’m fine,” he said. “It’ll heal. I’m staying here.”

I do not get angry easily, but at that, I lost it. “You are GOING!” I said. “You’re GOING if I have to DRAG YOU THERE.”

Paul looked flummoxed. “Sorry you have to hear that, Janina,” he said.

Janina is a recent widow; she lost her husband last year. He was a good man with some serious health issues, and they caught up to him, blindsiding her and the rest of the family. She paused as she arranged her cleaning supplies. “Maybe I should have yelled at my husband more,” she said.

Paul, for once, had no reply.

So we went to the VA. Where they spent a long time stitching layers of the top of his finger back together, then wrapping his hand in so much gauze that it looked like one of those oversized foam We’re-Number-One pointy-fingers from a football game. They gave him a regimen of antibiotics to prevent the infection he might’ve picked up while he Zoomed and dithered.

So here we are. Friends and neighbors ask about his wound; he tells them how he injured himself cutting my flowers, and they shake their heads and commiserate. Strangers gawk at his bandages and smile in sympathy. I have a new knee and a cane, and I can’t compete with We’re-Number-One.